Participating Artists: Beatriz Jaramillo, Matthew Brandt, Ignacio Perez Muruane, Kim Abeles, Sarah Jenkins, Elena Soterakis, Julie Weitz, Romi Morrison, Zane Griffin, Talley Cooper and Katie Gressitt-Diaz, Noa Kaplan

SUPERCOLLIDER presents EXTRACTION: Earth, Ashes, Dust, an exhibition that examines the overarching power structures that dictate methods of removal as they relate to cultural, natural, and ecological capital. Artists challenge notions of the map, explore both healed and broken landscapes, and embody methods of extraction and regeneration. Using a range of media, the works excavate systems that disrupt the autonomy of bodies (human and more-than-human), and also consider the historical implications of extractive practices across industries and geographies.

Works by Elena Soterakis, Beatriz Jaramillo and Matthew Brandt consider the landscape as a site of slow violence. Soterakis illustrates urban oil extraction in the Jurassic Technology series and Fossil Fuel Removal in Inglewood, CA, by juxtaposing the archaic oil industry with the residential communities in Los Angeles who are most impacted by ecological toxicity. Soterakis’s paintings both highlight the antiquated nature of oil extraction, and elicit a sense of empathy for the machines that work tirelessly, questioning the current and future state of human and machine interfaces implicated by our energy needs.

Beatriz Jaramillo’s work investigates the exterior and interior tensions produced when humans break their connection to the natural world. Her porcelain sculptures are proxies for the solid yet delicate stratifications of Earth–made fragile through the modifications made by human activity, and the imposition of imagined borders.

Matthew Brandt’s photographic prints capture the powerful geothermal intensities that formed the glaciers of the Vatnajökull ice field. Exposing his images to fire and heat, these works act as fossil records of these wondrous ice forms on the verge of disappearing.

Sarah E. Jenkins, Zane Griffin Talley Cooper, and Katie Gressitt-Diaz reflect on the human aspects of resource extraction, focusing on the hidden labor of major industries. Jenkins’s stop-motion experimental animations contend with the human labor involved in coal mining and timber removal. Disappearing Acts nods to the invisibility of human labor that underpins our energy systems and the Appalachian communities that are impacted both by environmental toxicity and disappearing industries.

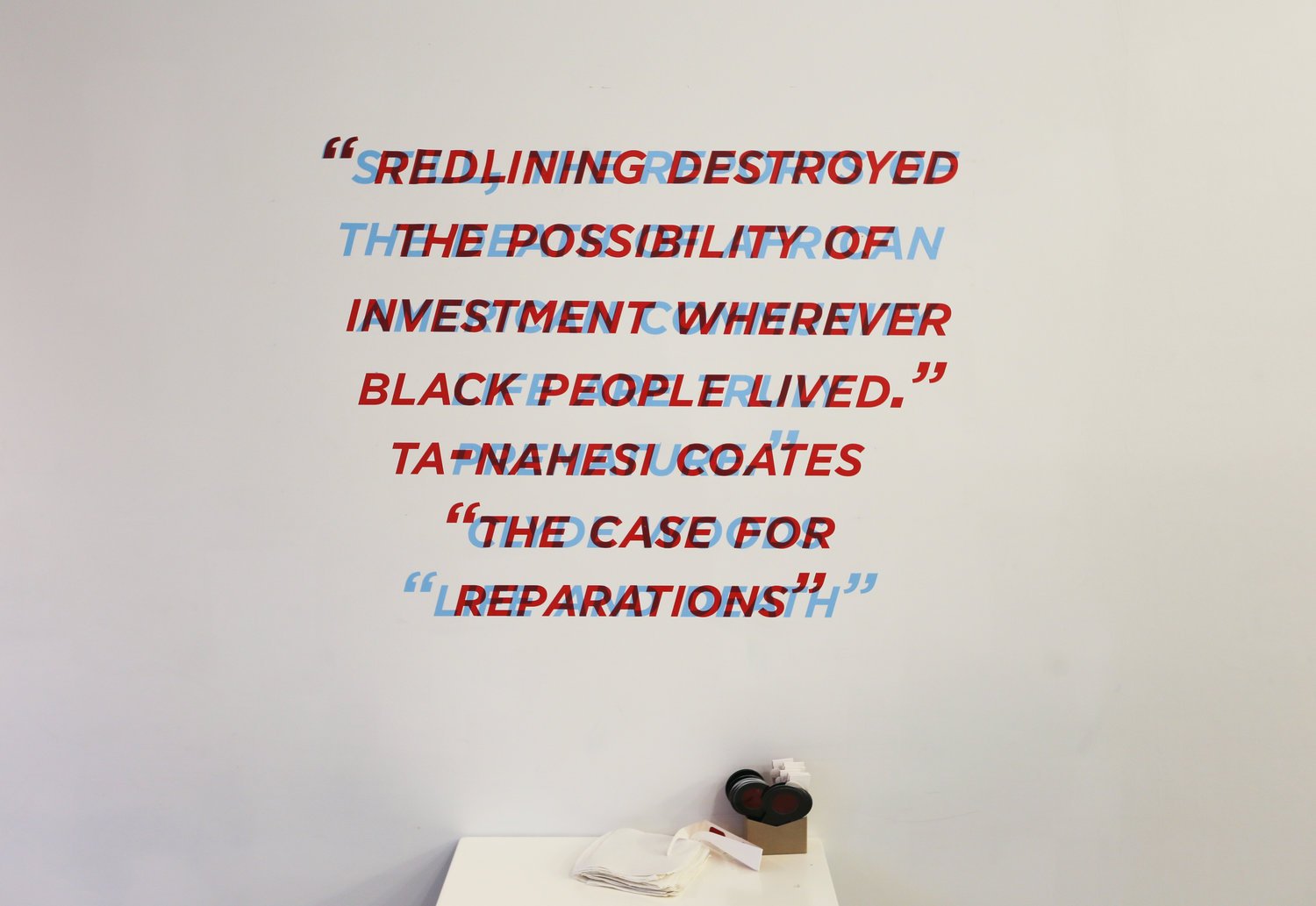

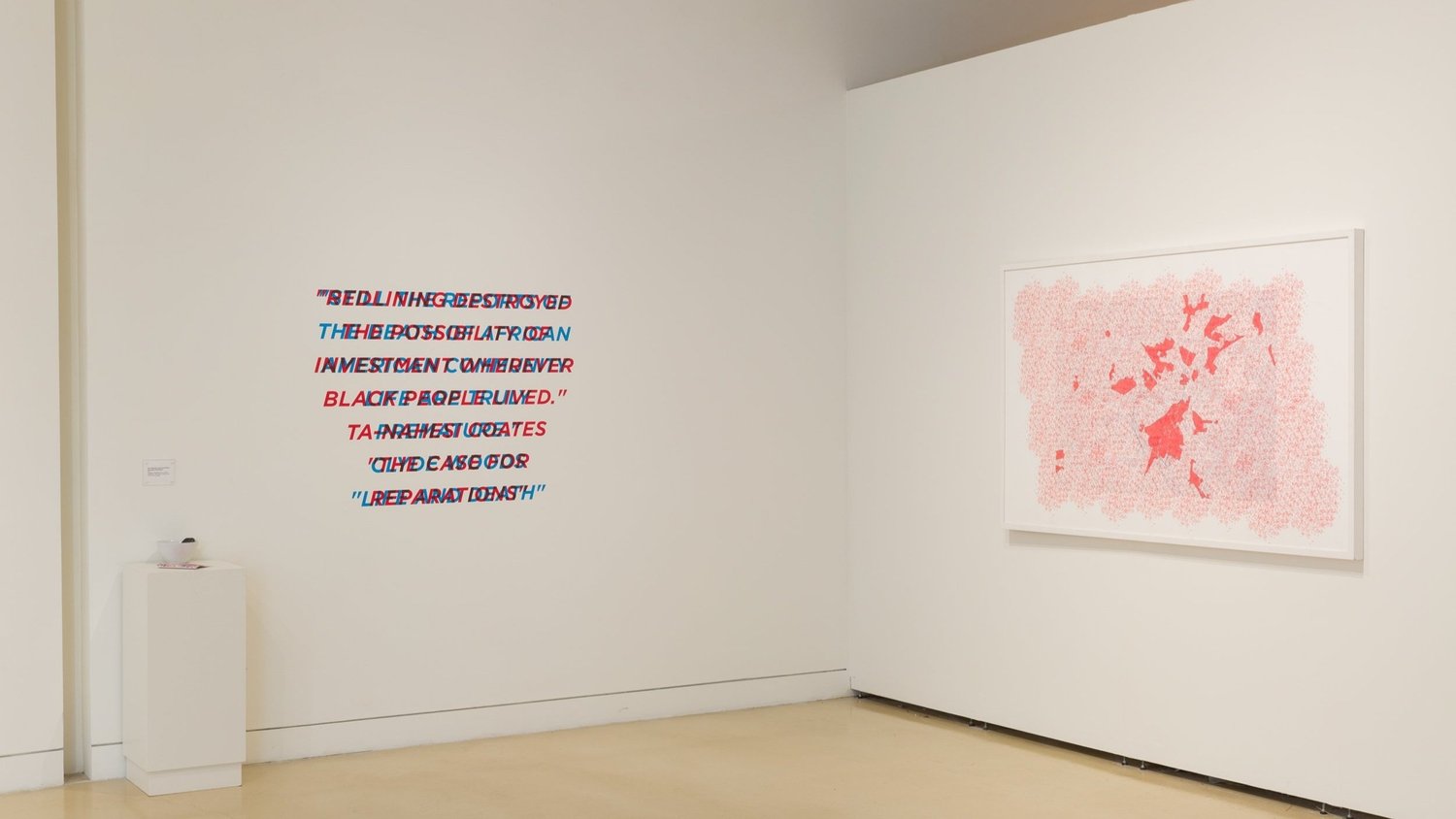

The exhibition considers the intricate ties between forms of extraction, highlighting the integrated nature of resources, bodies, and cultures. Romi Ron Morrison and Treva Ellison’s Decoding Possibilities visualizes red lining and gerrymandering as practices of cultural extraction and removal wherein social ties and political strength are thwarted by redistricting. The removal of political autonomy results in bifurcated communities and the forced erasure of socio-cultural identities, as well as the drive for social change.

Through the material copper, Ignacio Perez Meruane investigates the ties between local cultural production and corporate industrial practices. His sculptural installation Remove (Copper Art in the Andean World) traces the history of copper production in Chile from indigenous technologies to his own commentary on the complex relationship between copper extraction and cultural institutions in Chile.

Noa Kaplan, Kim Abeles, and Julie Weitz find inspiration in the detritus of progress and collapse. Noa Kaplan’s Quantification Sediment and Disaster Relief series utilize point cloud models of the Salton Sea as a point of departure for video and sculptural works – the glittering sand of the abandoned vacation site acting as a live fossil record of human-induced collapse.

Kim Abeles captures the very dust we breathe, in her Smog Collectors series (1987 – present). Placing stenciled images on rooftops, Abeles captures the pollution from the air, turning them into table settings, portraits of world leaders, and a replica of Asher Brown Durand’s “The Hunter”. They act as literal and metaphoric depictions of the industrial decisions that have caused the current conditions of our most important life source: the air we breathe.

Julie Weitz offers a healing ritual for the burnt, post-fire landscapes in her video Prayer for Burnt Forests. Using her character “My Golem”–a feminist and Chaplinesque embodiment of a traditional Jewish mythical creature–Weitz performs an original prayer and dance in the charred Tongva landscape in Southern California. Her work suggests that a way forward requires healing, reflection, and care.

This constellation of artistic expressions uniquely considers the many facets of late-stage capitalism, drawing connections between disparate entities–land, body, community–that expire in the pursuit of progress, the excitement of the new, and the movement of dominating forces towards mechanisms of control and erasure. These works express how hope exists in our rituals, our humanity, and the promise of liberation–for ourselves, the earth, and our communities.